When anxious feelings turn into an otherworldly experience – a personal view

What I remember most about my panic attacks is the sheer intensity of it all, enveloping everything around me. Excruciating light, unbearable noise, a feeling of suffocation. Internally, the same chaos unfolded as inexplicable dread spread over me, with my mind racing, my heart beating out of control and every single cell in my body ready to explode. Thankfully, most of the time, the anxiety would pass and the physical symptoms would follow. Other times, however, it would become uncontrollable, culminating in a new level of anxiety that would create the most unreal of all symptoms: an “out-of-body” experience.

Unreal reality

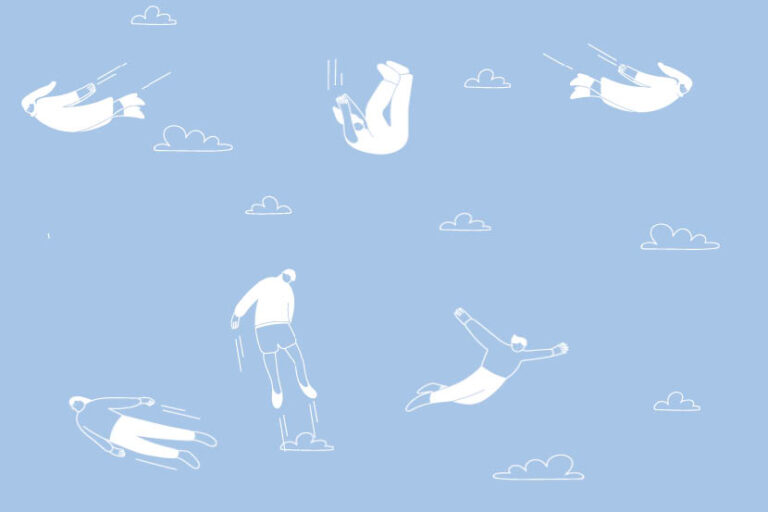

Imagine everything slowing down, the place becoming suddenly darker, the sound muted, people indistinct in the background. Something, somewhere, had snapped and I could no longer interpret my surroundings. Worst of all, I would suddenly find myself without thought, feeling or perception. Not only did I lose touch with reality, I would also lose my sense of identity. It felt as if my mind was disconnected from my body, as if I had been projected into a two-dimensional world, flat and still.

The feelings of terror that had engulfed me just a few seconds ago had now disappeared. But anxiety had pushed me over the edge and I felt completely empty and numb: I couldn’t feel my body, recognise my voice (not that I was able to utter many words), or hold on to any thoughts. I was paralysed and stuck in a protective bubble that felt like a dream at first, but quickly became a living nightmare. I felt I was losing my mind and there was something wrong with me. Only later it became clear that, actually, this had been a natural and instinctive self-preservation reaction.

Survival mode

This experience, known as dissociation, is one way the brain copes with too much stress during a traumatic experience. And if the brain feels compelled to react in the same way frequently, it can develop into a dissociative disorder, which manifests in different ways. The physical and emotional detachment experienced is called depersonalisation – you are there, but your sense of self has gone. The foggy and distorted world that usually comes with it is called derealisation. Again, you know where you are, but everything lacks colour and depth – like 2D rather than 3D.

Depersonalisation and derealisation are difficult to make sense of, but they are just the symptoms caused by the brain’s defence mechanism in times of stress and trauma. The mind has the power to switch itself off and go into survival mode.

Closing off

When faced with extreme anxiety, whatever the cause, the brain can go into overdrive. If it reaches a point when it can’t take any more, it can turn itself off. The result is beneficial as the symptoms stop in an instant – a mounting turmoil one minute, a surreal calm the next.

So when I couldn’t contain my mounting anxiety, my brain took me away from the “life-threatening” situation.

Having been overwhelmed, I was now looking at myself and the world from a distance. The brain’s essential functions may be running the body, but when it feels threatened, it can act drastically. Closing off is not a moment of weakness, but of self-preservation. But there is a cost: when your brain hits the emergency button, you are incapacitated physically and mentally.

Welcome back to 3D

I could never remember why my panic attacks triggered dissociation, how long it lasted or how I recovered. What I felt afterwards is also a mystery. Maybe that is another trick of the mind – relieved to have regained normality, it’s not yet ready to relive the highly disturbing experience.

Dissociation is often the lasting result of a trauma and it’s important to try to open up, first to yourself, but ideally with a specialised therapist, and find the courage to explore events that the brain has been trying to forget. Whatever the reason behind them, these traumas provoke an intense reaction.

Perhaps try to see an experience of dissociation as a sign to listen to your body and mind, to dig deep and uncover why you react this way. Because acknowledging your inner struggles will eventually allow you to make peace with yourself, to ease anxieties, and to move on.

If you have experiences similar to those described here, know that you are not alone and try to seek help. Make an appointment with your GP, or reach out to a support service like Beyond Blue at beyondblue.org.au, available 24/7 by phone on 1300 22 4636.